To kick off the year, I’ve finally been able to complete the draft of this AI Research Highlights of 2024 article. It covers a variety of topics, from mixture-of-experts models to new LLM scaling laws for precision.

Reflecting on all the major research highlights of 2024 would probably require writing an entire book. It’s been an extraordinarily productive year, even for such a fast-moving field. To keep things reasonably concise, I decided to focus exclusively on LLM research this year. But even then, how does one choose a subset of papers from such an eventful year? The simplest approach I could think of was to highlight one paper per month: January through December 2024.

So, in this article, I’ll share research papers that I personally found fascinating, impactful, or, ideally, both. However, note that this article is just Part One, focusing on the first half of 2024 from January through June. Part 2 of this series, covering July to December, will be shared later in January.

The selection criteria are admittedly subjective, based on what stood out to me this year. I’ve also aimed for some variety, so it’s not all just about LLM model releases.

If you’re looking for a broader list of AI research papers, feel free to check out my earlier article (LLM Research Papers: The 2024 List).

For those who read my previous article, I’m happy to share that I’m already feeling a bit better and slowly but steadily recovering! I also want to express my heartfelt thanks for all the kind wishes and support. It truly meant the world to me and helped me through some tough days!

Happy new year and happy reading!

1. January: Mixtral’s Mixture of Experts Approach

Only a few days into January 2024, the Mistral AI team shared the Mixtral of Experts paper (8 Jan 2024), which described Mixtral 8x7B, a Sparse Mixture of Experts (SMoE) model.

The paper and model were both very influential at the time, as Mixtral 8x7B was (one of) the first open-weight MoE LLMs with an impressive performance: it outperformed Llama 2 70B and GPT-3.5 across various benchmarks.

1.1 Understanding MoE models

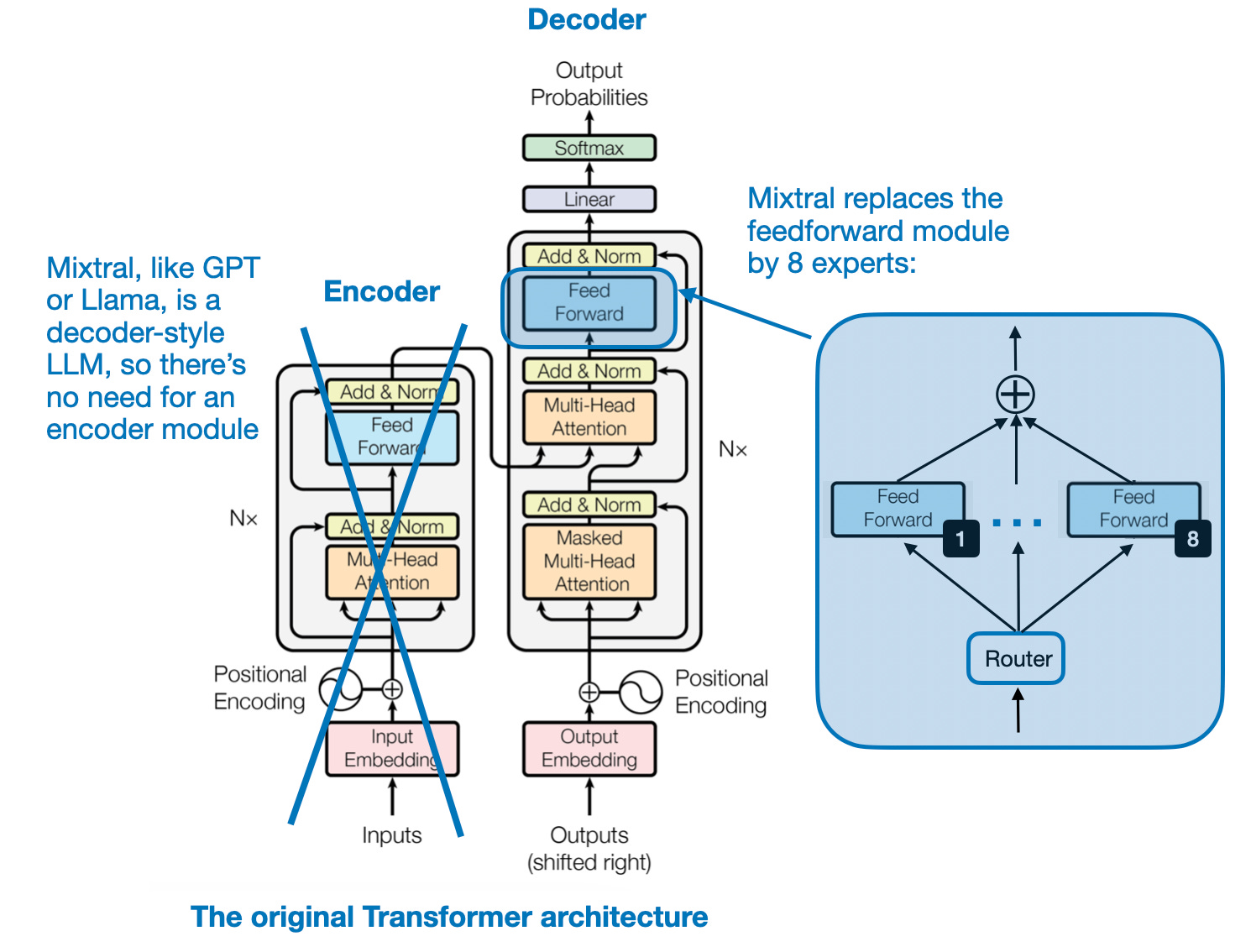

An MoE, or Mixture of Experts, is an ensemble model that combines several smaller “expert” subnetworks inside the GPT-like decoder architecture. Each subnetwork is said to be responsible for handling different types of tasks or, more concretely, tokens. The idea here is that by using multiple smaller subnetworks instead of one large network, MoEs aim to allocate computational resources more efficiently.

In particular, in Mixtral 8x7B, is to replace each feed-forward module in a transformer architecture with 8 expert layers, as illustrated in the figure below.

“Sparse” in the context of a “Sparse Mixture of Experts” refers to the fact that at any given time, only a subset of the expert layers (typically 1 or 2 out of the 8 in Mixtral 8x7B) are actively used for processing a token.

As illustrated in the figure above, the subnetworks replace the feed-forward module in the LLM. A feed-forward module is essentially a multilayer perceptron. In PyTorch-like pseudocode, it essentially looks like this:

class FeedForward(torch.nn.Module):

def __init__(self, embed_dim, coef):

super().__init__()

self.layers = nn.Sequential(

torch.nn.Linear(embed_dim, coef*embed_dim),

torch.nn.ReLU(),

torch.nn.Linear(coef*n_embed, embed_dim),

torch.nn.Dropout(dropout)

)

def forward(self, x):

return self.layers(x)

In addition, there is also a Router module (also known as a gating network) that redirects each of the token embeddings to the 8 expert feed-forward modules. The outputs from these 8 expert feed-forward layers are then summed, as illustrated in the figure below.

Since there are 11 more papers to cover in this article, I want to keep this description of the Mixtral model brief. However, you can find additional details in my previous article, Model Merging, Mixtures of Experts, and Towards Smaller LLMs.

1.2 The relevance of MoE models today

At the beginning of the year, I would have thought that open-weight MoE models would be more popular and widely used than they are today. While they are not irrelevant, many state-of-the-art models still rely on dense (traditional) LLMs rather than MoEs though, e.g., Llama 3, Qwen 2.5, Gemma 2, etc. However, it is, of course, impossible to say what proprietary architectures like GPT-4, Gemini, and Claude are based on; they might as well be using MoE under the hood.

In any case, MoE architectures are still relevant, especially as they offer a way to scale large language models efficiently by activating only a subset of the model’s parameters for each input, thus reducing computation costs without sacrificing model capacity.

By the way, after writing this article, there was a nice surprise release of the very well-performing DeepSeek-V3 model in December, which uses a MoE architecture. So, yes, MoEs continue to be very relevant!

2. February: Weight-decomposed LoRA

If you are finetuning open-weight LLMs, chances are high that you have been using low-rank adaptation (LoRA), a method for parameter-efficient LLM finetuning, at some point.

If you are new to LoRA, I have written a previous article on Practical Tips for Finetuning LLMs Using LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) that you might helpful, and I have a from-scratch code implementation in Appendix D of my Build A Large Language Model (From Scratch) book.

Since LoRA is such a popular and widely used method, and since I had so much fun implementing and playing with a newer variant, my pick for February is DoRA: Weight-Decomposed Low-Rank Adaptation (February 2024) by Liu and colleagues.

2.2 LoRA Recap

Before introducing DoRA, here’s a quick LoRA refresher:

Full finetuning updates each large weight matrix W in an LLM by computing a large weight update matrix ΔW. LoRA approximates ΔW as the product of two smaller matrices A and B. So, Instead of W + ΔW, we have W + A.B. This greatly reduces computational and memory overhead.

The figure below illustrates these formulas for full finetuning (left) and LoRA (right) side by side.

2.2 From LoRA to DoRA

In DoRA: Weight-Decomposed Low-Rank Adaptation (February 2024), Liu and colleagues.extend LoRA by first decomposing a pretrained weight matrix into two parts: a magnitude vector m and a directional matrix V. This decomposition is rooted in the idea that any vector can be represented by its length (magnitude) and direction (orientation), and here we apply it to each column vector of a weight matrix. Once we have m and V, DoRA applies LoRA-style low-rank updates only to the directional matrix V, while allowing the magnitude vector m to be trained separately.

This two-step approach gives DoRA more flexibility than standard LoRA. Rather than uniformly scaling both magnitude and direction as LoRA tends to do, DoRA can make subtle directional adjustments without necessarily increasing the magnitude. The result is improved performance and robustness, as DoRA can outperform LoRA even when using fewer parameters and is less sensitive to the choice of rank.

Again, I am keeping this section brief since there are 10 more to go, but if you are interested in additional details, I dedicated a whole article to this method earlier this year: Improving LoRA: Implementing Weight-Decomposed Low-Rank Adaptation (DoRA) from Scratch.

2.3 The future of LoRA and LoRA-like methods

DoRA is a small, logical improvement over the original LoRA method. While it hasn’t been widely adopted yet, it adds minimal complexity and is worth considering the next time you finetune an LLM. In general, I expect LoRA and similar methods to remain popular. For example, Apple recently mentioned in their Apple Intelligence Foundation Language Models paper that they use LoRA for on-device task specialization of LLMs.

3. March: Tips for Continually Pretraining LLMs

As far as I can tell, instruction-finetuning is the most popular form of finetuning by LLM practitioners. The goal here is to get openly available LLMs to better follow instructions or specialize these LLMs on subsets or new instructions.

However, when it comes to taking in new knowledge, continued pretraining (sometimes also referred to continually pretraining) is the way to go.

In this section, I want to briefly summarize the refreshingly straightforward Simple and Scalable Strategies to Continually Pre-train Large Language Models (March 2024) paper by Ibrahim and colleagues.

3.1 Simple techniques work

This 24-page Continually Pre-train Large Language Models paper reports a large number of experiments and comes with countless figures, which is very thorough for today’s standards.

What were the main tips for applying continued pretraining successfully?

1. Simple re-warming and re-decaying the learning rate.

2. Adding a small portion (e.g., 5%) of the original pretraining data to the new dataset to prevent catastrophic forgetting. Note that smaller fractions like 0.5% and 1% were also effective.

To be a bit more concrete regarding point 1, re-warming and re-decaying, this means we employ the exact same learning rate schedule that was used during the initial pretraining stage of an LLM as shown in the figure below.

As far as I know, the re-warming and re-decaying, as well as adding original pretraining data to the new data, is more or less common knowledge. However, I really appreciate that the researchers took the time to formally test this method in this very detailed 24-page report.

If you are interested in additional details, I discussed this paper more thoroughly in my previous Tips for LLM Pretraining and Evaluating Reward Models article.

3.2 Will these simple techniques continue to work?

I have no reason to believe that these methods will not continue to work for future LLMs. However, it is important to note that pretraining pipelines have become more sophisticated in recent months, consisting of multiple stages, including short- and long-context pretraining. (I’ve written more about it in New LLM Pre-training and Post-training Paradigms).

So, for optimal results, the recipes suggested in this paper may need to be tweaked under certain circumstances.

4. April: DPO or PPO for LLM alignment, or both?

April is a tough choice. For instance, Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks made a big wave that month. But as far as I can tell, the excitement fizzled out pretty quickly. This is likely because their theoretical guarantees are difficult to implement practically, they lack competitive results or benchmarks, and other architectures are much more scalable.

So, instead, my pick for April goes to a more practical paper: Is DPO Superior to PPO for LLM Alignment? A Comprehensive Study (April 2024) by Xu and colleagues.

4.1 RLHF-PPO and DPO: What Are They?

Before summarizing the paper itself, here’s an overview of Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) and Direct Preference Optimization (DPO), both popular methods in aligning LLMs via Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF). RLHF is the method of choice to align LLMs with human preferences, improving the quality but also the safety of their responses.

Traditionally, RLHF-PPO has been a crucial step in training LLMs for models and platforms like InstructGPT and ChatGPT. However, DPO started gaining traction last year due to its simplicity and effectiveness. In contrast to RLHF-PPO, DPO does not require a separate reward model. Instead, it directly updates the LLM using a classification-like objective. Many LLMs now utilize DPO, although comprehensive comparisons with PPO are lacking.

Below are two resources on RLHF and DPO I developed and shared earlier this year:

LLM Training: RLHF and Its Alternatives

Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) for LLM Alignment (From Scratch)

4.2 PPO Typically Outperforms DPO

Is DPO Superior to PPO for LLM Alignment? A Comprehensive Study is a well-written paper with numerous experiments and results. The key conclusions are that PPO tends to outperform DPO, and that DPO is inferior when dealing with out-of-distribution data.

Here, out-of-distribution data means the language model was previously trained on instruction data (via supervised finetuning) that differs from the preference data used for DPO. For instance, a model might be trained on the general Alpaca dataset before undergoing DPO finetuning on a different preference-labeled dataset. (However, one way to improve DPO on such out-of-distribution data is to first conduct a supervised instruction-finetuning step using the preference dataset, and then perform DPO finetuning.)

The main findings are summarized in the figure below.

4.3 How are PPO and DPO used today?

PPO might have a slight edge when it comes to the raw modeling performance of the resulting LLM. However, DPO is much easier to implement and computationally more efficient to apply (you don’t have to train and use a separate reward model, after all). Hence, to the best of my knowledge, DPO is also much more widely used in practice than RLHF-PPO.

One interesting example is Meta AI’s Llama models. While Llama 2 was trained with RLHF-PPO, the newer Llama 3 models used DPO.

Interestingly, recent models even use both PPO and DPO nowadays. Recent examples include Apple’s Foundation Models and Allen AI’s Tulu 3.

5. May: LoRA learns less and forgets less

I found another LoRA paper this year particularly interesting (this is the last LoRA paper in this 12-paper selection, I promise!). I wouldn’t call it groundbreaking, but I really like it since it formalizes some of the common knowledge around finetuning LLMs with (and without) LoRA: LoRA Learns Less and Forgets Less (May 2024) by Biderman and colleagues.

LoRA Learns Less and Forgets Less is an empirical study comparing low-rank adaptation (LoRA) to full finetuning on large language models (LLMs), focusing on two domains (programming and mathematics) and two tasks (instruction finetuning and continued pretraining). Check out the February section above if you’d like a refresher on LoRA before proceeding.

5.1 LoRA learns less

The LoRA Learns Less and Forgets Less study shows LoRA learns noticeably less than full finetuning, especially in tasks like coding, where new knowledge needs to be acquired. The gap is smaller when only instruction finetuning is performed. This suggests that pretraining on new data (learning new knowledge) benefit more from full finetuning than converting a pretrained model into an instruction follower.

There are some more nuances, though. For math tasks, for example, the difference between LoRA and full finetuning shrinks. This may be because math problems are more familiar to the LLM, and they likely encountered similar problems during pretraining. In contrast, coding involves a more distinct domain, requiring more new knowledge. Thus, the farther a new task is from the model’s pretraining data, the more beneficial full finetuning becomes in terms of learning capacity.

5.2 LoRA forgets less

When examining how much previously acquired knowledge is lost, LoRA consistently forgets less. This is particularly clear when adapting to data far from the source domain (e.g., coding). With coding tasks, full finetuning leads to significant forgetting, while LoRA preserves more original capabilities. In math, where the model’s original knowledge was already closer to the new task, the difference is less pronounced.

5.3 The LoRA trade-off

Overall, there is a trade-off: full finetuning is better for absorbing new knowledge from more distant domains but leads to more forgetting of previously learned tasks. LoRA, by changing fewer parameters, learns less new information but retains more of the original capabilities.

5.4 Future approaches to finetuning LLMs

The study primarily compares LoRA to full finetuning. In practice, LoRA has gained popularity because it is far more resource-efficient than full finetuning. In many cases, full finetuning is simply not feasible due to hardware constraints. Moreover, if you only need to address specialized applications, LoRA alone may be sufficient. Since LoRA adapters can be stored separately from the base LLM, it’s easy to preserve the original capabilities while adding new ones. Additionally, it’s possible to combine both methods by using full finetuning for knowledge updates and LoRA for subsequent specialization.

In short, I think both methods will continue to be very relevant in the upcoming year(s). It’s more about using the right approach for the task at hand.

6. June: The 15 Trillion Token FineWeb Dataset

The FineWeb Datasets: Decanting the Web for the Finest Text Data at Scale (June 2024) paper by Penedo and colleagues describes the creation of a 15 trillion token dataset for LLMs and making it publicly available, including a link to download the dataset and a code repository (datatrove/examples/fineweb.py) to reproduce the dataset preparation steps.

6.1 Comparison to other datasets

Since several other large datasets for LLM pretraining are available, what’s so special about this one? Other datasets are comparatively small: RefinedWeb (500B tokens), C4 (172B tokens), the Common Crawl-based part of Dolma 1.6 (3T tokens) and 1.7 (1.2T tokens), The Pile (340B tokens), SlimPajama (627B tokens), the deduplicated variant of RedPajama (20T tokens), English CommonCrawl section of Matrix (1.3T tokens), English CC-100 (70B tokens), Colossal-OSCAR (850B tokens).

For example, ~360 billion tokens are only suited for small LLMs (for instance, 1.7 B, according to the Chinchilla scaling laws). On the other hand, the 15 trillion tokens in the FineWeb dataset should be optimal for models up to 500 billion parameters according to the Chinchilla scaling laws. (Note that RedPajama contains 20 trillion tokens, but the researchers found that models trained on RedPajama result in poorer quality than FineWeb due to the different filtering rules applied.)

In short, the FineWeb dataset (English-only) makes it theoretically possible for researchers and practitioners to train large-scale LLMs. (Side note: The Llama 3 models with 8B, 70B, and 405B sizes were trained on 15 trillion tokens as well, but Meta AI’s training dataset is not publicly available.)

6.2 Principled dataset development

In addition, the paper contains principled ablation studies and insights into how the filtering rules were developed and applied to arrive at the FineWeb dataset (starting from the CommonCrawl web corpus). In short, for each filtering rule they tried, they took a 360 billion token random sample from the original and the filtered data and then trained a small 1.71 billion parameter Llama-like model to see whether the filtering rule is beneficial or not based on the models’ performances on standard benchmarks such as HellaSwag, ARC, MMLU, and others.

6.3 The relevance of FineWeb today

Overall, while pretraining multi-billion parameter LLMs may still be beyond the reach of most research labs and companies, this dataset is a substantial step toward democratizing the study and development of LLMs. In summary, this paper represents a commendable effort and introduces a valuable public resource for advancing pretraining in LLMs.

July to December

I hope you found the research summaries useful! Since I am still recovering from my injury, and since it would have been an excessively long article anyway, I decided to split this year’s review article into two parts.

The second (July to December) part is actually even more exciting (for me personally), as I am discussing the more recent papers on scaling laws, reproducing O1, and the role of synthetic data in LLM training. In addition, I will also share my thoughts for 2025 and what I expect to be on the horizon. Stay tuned!

This magazine is a personal passion project. For those who wish to support me, please consider purchasing a copy of my Build a Large Language Model (From Scratch) book. (I am confident that you’ll get lots out of this book as it explains how LLMs work in a level of detail that is not found anywhere else.)

If you read the book and have a few minutes to spare, I’d really appreciate a brief review. It helps us authors a lot!

Your support means a great deal! Thank you!